Tips and Tools for Young Students to Start Engaging in Science, Technology, Engineering and Math

It seems there’s no shortage of opportunities for STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Math) and STEAM (just add Art for the A) learning for elementary, middle, and high school students these days. It’s become the focus of entire schools, teacher-sponsored clubs, and after-school programs, and with good reason: Children who learn STEM concepts throughout their education are better prepared to meet increasingly technology-focused professional requirements, according to an article from American University’s School of Education.

But what about early childhood? Is it unreasonable to teach babies, toddlers and preschoolers complex concepts of science, technology, engineering, and math? Experts agree it’s never too early to begin, but the way these concepts are introduced to early learners is different. According to the same American University article: At its core, STEM concepts help children develop new ways of thinking, encouraging curiosity and analysis—it’s not just about introducing them to new subjects. Establishing these skills at an early age (infancy through third grade), when young minds are most malleable, establishes lifelong thinking skills.

And while there are many ways to teach different STEM concepts, the overall goal at any age is to move away from rote memorization toward project-based learning that sparks students’ imaginations and develops their real-world skills.

“I think a big reason why kids struggle in STEM later is because they weren’t around it enough when they were young and then find it intimidating,” says Kayla Opperman, owner of Snapology of Golden-Littleton, a company that offers STEM-based workshops and camps to young students. “I don’t think it’s ever too early to start! There’s always an opportunity to point STEM concepts out and make it fun…They learn best when having fun and when not even realizing it’s educational.”

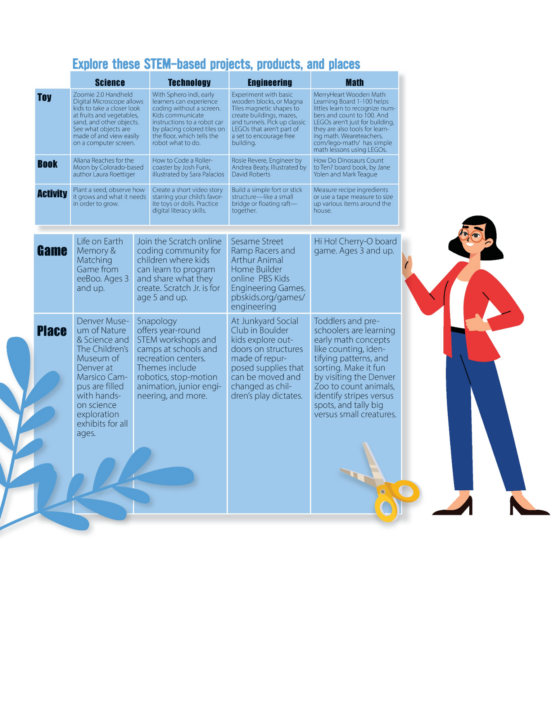

Consider the following for your early learners, to help them do just that.

Encourage and model curiosity. With more than 35 years experience working with and raising children, Colorado-based reading specialist and STEM author Laura Roettiger thinks encouraging curiosity is the single most important thing a parent can do to encourage an interest in STEM subjects. “Curiosity will take that child in whatever direction they are meant to go,” she says. With her own daughter, now a mechanical engineer, Roettiger remembers that she was always curious about how things fit together as a child and always wanted to build things. “I said, ‘sure, give it a try.’ I was not the parent that said, ‘No, you’ll make a mess or you’ll break something.’” It’s also the message she conveys in her STEM-themed book, Aliana Reaches for the Moon.

Roettiger thinks it’s important for adults to model this curiosity for their own interests, too. Tell kids how you learn things when you are curious, whether that’s through internet research, going to a museum or nature center, or by asking experts. “If we are interested, how do we learn?” she asks.

Provide opportunities for exploration and hands-on learning. “I believe the most effective way for kids to learn STEM concepts is through hands-on, interactive play,” Opperman says. “I think Lego bricks are perfect for learning math, as they’ll probably have an easier time with fractions later if they build during the early years. Technic bricks and gears will help them understand basic physics concepts later on.”

As a former electrical engineer, Opperman loves teaching kids robotics and watching their wheels turn as they put together the pieces. “The programming part brings it all together, and they get to understand how gear ratio, sensors, motors, wheels, axles, and more work. Snapology teaches children, as young as four, robotics, and even that age can stay engaged if you make it fun, and if they know what the end product is going to be.”

Roettiger suggests slowing down to give very young kids opportunities to explore their surroundings. Show infants the different feeling of warm and cold by putting their hands under the faucet. Sniff spices or walk by the bakery to experience different smells.

“Children are born scientists,” Roettiger says. “Think about the way a child looks at the world. They pick up a leaf, drop it, and watch it float to the ground. That same child picks up a rock and watches it fall faster. This is all information gathering and making sense of their world. As parents, caregivers, and educators we need to honor the child’s innate motivation to learn about their world.”

As a preschool teacher at Colorado STEM Academy in Westminster, Stevi Caridi sees firsthand how her four- and five-year-old students learn best when given the opportunity to “see and touch and do, rather than sitting and getting,” she says. Her school uses a curriculum called Project Lead The Way, which incorporates various challenges for young children to solve, along with the physical materials to go with them.

One of the final projects for her preschoolers is making a cast for a child’s arm. Working in pairs, they create something that is waterproof and supports the arm. She adds that when it comes to learning STEM concepts, it needs to be projects that are relatable to a child’s world, that they are able to test themselves.

Ask questions about their process, and let them take the lead.

Caridi finds that these projects and problems in the curriculum work best when they are student-led and guided by teachers. She says that when her preschoolers get frustrated, she helps them by asking questions that could help develop their problem solving skills. For example, if they are building a house with popsicle sticks and it’s not coming together as they planned, she might ask, “how many walls does a house have?” rather than telling them what to do. She pairs this with building their confidence when they figure something out: “You’re right, a house does have four walls!”

“You just give them a little direction, and their mind goes crazy,” she says. “It’s so different from when I was in school, with just sitting and listening, and not as much hands-on exploration. Here, we see problem solving and collaboration.”